NEURO-ANATOMY OF THE VAGUS

If you were to peruse the internet, or, for that matter, medical textbooks, looking for images of the Vagus nerve, you would come away with the impression that it is, as it sounds like from the name, a single nerve. When we learn about nerves in neurobiology, the template from which the conceptualization arises is based on the neuron, and the template of the neuron is a cell that has short dendrites to receive input signals, and a long axon. We tend to think of neurons as having long rope-like tails, and we tend to think of nerves in a similar manner: as telephone wires that connect distant parts of the body like so many telephone lines spanning the interstices between parts of us. Yet the reality is so much more complex. Nerve cells come in such a radical proliferation of types that if you couldn't recognize their functional equivalence you wouldn't be able to class them together based on appearance, because they do not look anything alike, and many of them don't look much of anything like what we are taught a neuron looks like. This is important, because, similarly, the Vagus nerve looks nothing like a telephone wire. It looks more like a cloud of cotton candy woven through all the organs of the viscera.

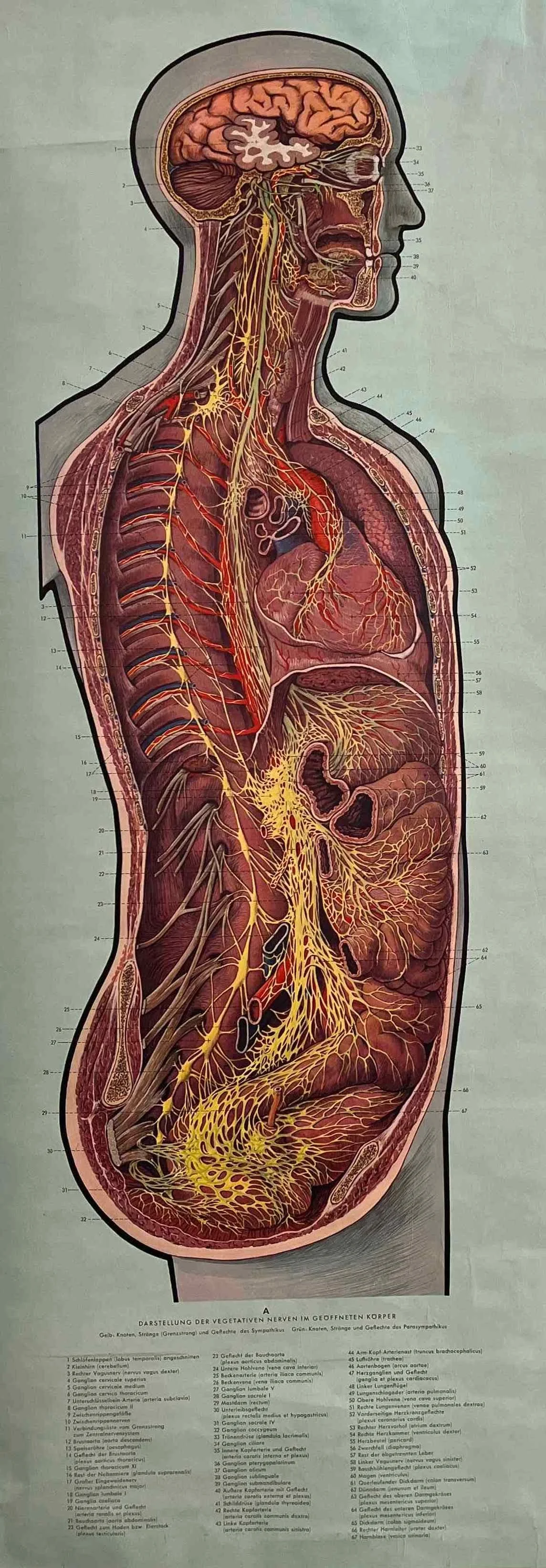

Above is a standard representation of the Vagus, what you would find if you performed an image search or looked at most physiology textbooks. This is not anything close to what the living Vagus actually looks like.

One of the challenges of our (possibly?) necessarily reductionistic desire to simplify the systems of the human body so that we can understand them is that this abridging often denatures something fundamental about them, obscuring the multiple ways in which they actually work. If we think about the Vagus as a 'wandering nerve', we end up with a mental representation of it that is so far away from the neuro-anatomical reality as to actually obscure a direct experiential understanding of what the Vagus is, and what it is doing.

The illustration above is accurate in as much as it correctly illustrates the brainstem connectivity of the vagus, it’s bi-laterality, and its innervation of visceral organs. 70-80% of vagal fibers are afferent, monitoring bodily processes, and we can see that the vagus touches the internal organs, so that is accurate enough. Yet it is also distortional in a way that largely precludes your understanding of how the Vagus actually works. In reality, the Vagus is as different from this illustration as the Oak in winter, with no leaves, is from the Oak in summer, when most of what you see are leaves.

The reason that I know about this, which is connected to the reason that I care about this, is that in 2020 I lead a working group collaborating with Stephen W. Porges, PhD to develop a neuro-anatomically accurate illustration of the Polyvagal Theory. I thought this would take about three weeks. It ended up taking nine months, and in the process we rejected 18 versions of the illustrations. With respect to the neuro-anatomical illustrations, it became evident along this road that the functional anatomical diagrams being taught in medical school are grossly inaccurate. We discovered this, in part, through interoception, because I was able to feel parts of my own vagal system from inside that the allopathic medical diagrams suggested did not exist until I began to scour the internet, and anatomical texts at every library I could access, for alternate illustrations of the Autonomic Nervous System.

Eventually this led me to a reprint of an Atlas of Anatomy and Surgery published between 1831 and 1854, originally in French, by J.M. Bourgery & N.H. Jacob, which has been called, “The most beautiful anatomical treatise in history,” and was republished by the German art publisher Taschen. We can imagine that surgeons in training need accurate maps in order to not accidentally sever nerves. The illustrations that I discovered therein accorded with my own interoceptive experience, and completely altered my understanding of the anatomy of these systems.

Let us first remember that until it terminates in a target organ, it is very difficult say where a nerve ends. The name may change at a plexus where multiple nerves come together, but if the signals are bi-directionally moving through this system, it is functionally the same nerve. The highway doesn't stop at an exit ramp. The street name might change, but the signals are moving seamlessly from one to another. The vagus is, in reality, a neural scaffolding that ensheaths all of the visceral organs. If you could see it in its completeness, it would much more closely resemble cotton candy, or a cobweb, than a wire. It is literally woven through, and around all of the visceral organs, because it is sensing them and governing them in coordination with chemical signals from the endocrine and immune systems. Like a great tree that begins with a trunk, that moves into massive branches, that ramify into smaller branches, that ramify into smaller branches yet, that finally leaf out, the living Vagus is the Oak in summer version of you. What am I saying? Most of your body is woven through with...the Vagus.

I’m using the image above from a German publisher printed in 1964 because it is provisionally accurate, and not under copyright anymore. The Bourgery images have been reprinted by Taschen (see link above). Thanks to Jane Garcia who unearthed the poster above in Vienna. Much appreciated.

Note that although the image above is closer to what I am describing, it is still trunk lines and branches. It is not possible to illustrate the living Vagus that I am describing. It innervates, for example, cutaneous autonomic receptors in the skin that are so dense there are nine square yards of them per square inch. If the average body surface area of an adult is 1.75 square meters, that means that we have 24,500 meters of c-tactiles woven through the surface of our body (thanks to Jeff Rockwell DC MA DOMP for this awareness). If I made you a neuro-anatomically accurate map of your living Vagus, it would simply be a neuro-anatomical abstract of your entire body. We don’t understand this because we have all learned neuro-anatomy from cadavers.

You (even if you have studied neuroscience with the finest teachers in the world, which I have) have been taught a necrotic neuro-anatomy; not the neuro-anatomy of living systems.

Your living Vagus is as splendid as virgin rainforest, a natural embodied cathedral of such grand majesty as to be almost incomprehensible in its vastness. Unfortunately, most modern people are not using this aboriginal neural inheritance wisely because we are so inundated by threat as to be unable to access most of its wonder. The Vagus is your vast interoceptive sensing network: the seat of embodied intelligence, home of your visceral awareness. Yet pushed into defense, most of us are merely utilizing it as an alarm system when it can be the doorway to coming home to ourselves.

You possess among the most elaborate relational embodied intelligences in the world, and the toxic context of modernity is causing you to primarily use it as an alarm system.